A while back I posted about my new hero, the songwriter and keyboardist Billy Preston. Back then I wasn't as web-savvy. What's more, lo, these last five months, the amount of streaming music and video on the web has increased exponentially (okay, perhaps not that much, but try to prove me wrong). Anyways, back then you had to take my word for it that Billy Preston was worthy of worship. Now I can prove it. Check out the following clip from George Harrison's fabled Concert for Bangladesh. Watch it all the way through, if you've got time and patience for it:

Billy Preston - That's The Way God Planned It

Now that's an amazing performance, you must admit, even if gospel-infused R&B isn't your cup of proverbial tea (Get it? infused? tea? Boy, sleep deprivation is a wild ride!) I have to say, that performance puts the fear of God in this atheist's soul, not that I believe I have one.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

The Hinsdale-Wheaton Isogloss Bundle

A few weeks or maybe months ago there was some discussion over at Language Log about the complex intersection of the terms "blog," "blawg" and the low-back merger, which linguists call the "cot/caught" merger, and which Argotnaut calls the "hottie/haughty" merger, a merger I've touched on here. The complexity I wasn't aware of -- well, one of many -- is that people who distinguish between these vowels don't always agree on which word has which vowel. For instance, the vowels in "Chicago" and "sausage" for me are "caught" vowels, whereas for others they are "cot" vowels.

Thus, when in a recent email my mother coined the term "blahg" -- get it? I had to find out how she pronounced it, so I asked her, ever so innocently (This blog is a secret: don't tell my parents! Or my adviser!) if "blahg" and "blog" are pronounced the same. She said they were.

Does this mean she has the "cot/caught" merger? No, and I can attest she doesn't, nor should she; she's from Barrington, Illinois, what was a small town when she lived there and is now an outer northwest suburb of Chicago, definitively in unmerged territory. Rather, this means that "blog" and, implicitly, "log" in her dialect have the "cot" vowel. Me, I would definitely pronounce "blahg" and "blog" differently -- "log" and "blog" are "caught" words for me.

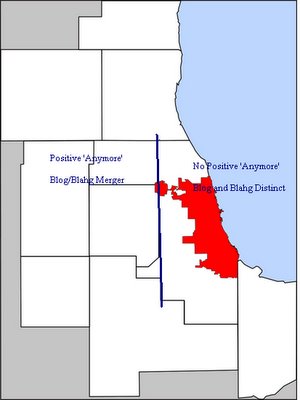

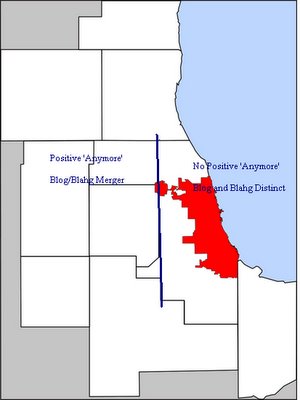

Thus I propose that there is an isogloss dividing the western suburbs of Chicago from the rest of the Chicagoland area, which I will call the "blahg/blog" isogloss. Since I am making up facts, I will further suggest that this isogloss is in the same place as the one delimiting the occurrence of positive 'anymore' in Chicagoland. So we see that there is actually an isogloss bundle running roughly (why not?) along I-294, or maybe the Cook/Du Page county line. This isogloss reflects cultural differences and historic settlement patterns, though I can't say which ones. Boy, making up facts is fun. Here's a map:

How's that for armchair dialectology? The closest thing to data behind this map comes from my Positive 'Anymore' Unscientific Survey Experiment (PAUSE), which clearly shows that people from the city of Chicago and the inner suburbs think they don't use positive 'anymore' and in fact probably don't, though anymore it's hard to tell.

Thus, when in a recent email my mother coined the term "blahg" -- get it? I had to find out how she pronounced it, so I asked her, ever so innocently (This blog is a secret: don't tell my parents! Or my adviser!) if "blahg" and "blog" are pronounced the same. She said they were.

Does this mean she has the "cot/caught" merger? No, and I can attest she doesn't, nor should she; she's from Barrington, Illinois, what was a small town when she lived there and is now an outer northwest suburb of Chicago, definitively in unmerged territory. Rather, this means that "blog" and, implicitly, "log" in her dialect have the "cot" vowel. Me, I would definitely pronounce "blahg" and "blog" differently -- "log" and "blog" are "caught" words for me.

Thus I propose that there is an isogloss dividing the western suburbs of Chicago from the rest of the Chicagoland area, which I will call the "blahg/blog" isogloss. Since I am making up facts, I will further suggest that this isogloss is in the same place as the one delimiting the occurrence of positive 'anymore' in Chicagoland. So we see that there is actually an isogloss bundle running roughly (why not?) along I-294, or maybe the Cook/Du Page county line. This isogloss reflects cultural differences and historic settlement patterns, though I can't say which ones. Boy, making up facts is fun. Here's a map:

How's that for armchair dialectology? The closest thing to data behind this map comes from my Positive 'Anymore' Unscientific Survey Experiment (PAUSE), which clearly shows that people from the city of Chicago and the inner suburbs think they don't use positive 'anymore' and in fact probably don't, though anymore it's hard to tell.

Sunday, March 26, 2006

Ringe Range Rouzi

One of the coolest things I've found recently is a Hasidic online forum in Yiddish called "kinderishe geredekhts" - chilren's sayings. People write in, posting their memories of things they remember saying as children. Personally, I love children's sayings - it's a bit of real, vibrant folklore that we've all participated in firsthand. Sometimes children's sayings can be surprising. For instance, my wife, attending to a one-room schoolhouse (really) that was fifteen miles from the nearest post office, learned the same bit of doggerel that I did on the South Side of Chicago:

Monchichi monchichi

I can play Atari

Monchichi monchichi

I can do karate

Monchichi monchichi

Oops I'm sorry

How and why did this piece of nonsense spread so widely? I don't know, but it did. Weird, no? A lot of the Hasidic children's sayings are equally strange, but what fascinates me most is the interplay between Eastern European and American elements. Some of the sayings I know from scholarly studies of Yiddish children's sayings, others are English ones I knew growing up. Then there is the following:

רינגע ראנגע ראוזי פאקע פאלע פאוזי, עשעס עשעס ווי אלל פאל דאון

"Ringe range rouzi pake fole pouzi, eshes eshes vi all fal daun."

Pretty darn cool.

Even cooler is the ensuing discussion. The poster asks if anyone has heard the rumor that this has to do with idolatry. Someone else writes in to say that he read in "Mallos" (a Hasidic magazine) that this rhyme comes from "the church," and that the "falling down" at the end has to do with bowing down, a big taboo in Judaism, such a big no-no that the poster adds an acronym רח''ל meaning, roughly, 'God forbid' - for merely having mentioned bowing down. Someone else writes

This prompts someone to post a link to Snopes where they debunk the story that "Ring Around the Rosie" has anything to do with any plague.

A heck of a journey, all told. From suspicious rumors of idolatry to widespread urban legends to Snopes. All within a week. This is the revolution the internet is causing in the Hasidic world - an instant acceleration to light speed. And we get to watch.

Monchichi monchichi

I can play Atari

Monchichi monchichi

I can do karate

Monchichi monchichi

Oops I'm sorry

How and why did this piece of nonsense spread so widely? I don't know, but it did. Weird, no? A lot of the Hasidic children's sayings are equally strange, but what fascinates me most is the interplay between Eastern European and American elements. Some of the sayings I know from scholarly studies of Yiddish children's sayings, others are English ones I knew growing up. Then there is the following:

רינגע ראנגע ראוזי פאקע פאלע פאוזי, עשעס עשעס ווי אלל פאל דאון

"Ringe range rouzi pake fole pouzi, eshes eshes vi all fal daun."

Pretty darn cool.

Even cooler is the ensuing discussion. The poster asks if anyone has heard the rumor that this has to do with idolatry. Someone else writes in to say that he read in "Mallos" (a Hasidic magazine) that this rhyme comes from "the church," and that the "falling down" at the end has to do with bowing down, a big taboo in Judaism, such a big no-no that the poster adds an acronym רח''ל meaning, roughly, 'God forbid' - for merely having mentioned bowing down. Someone else writes

The legend that 'Ring a ring a rozi" has to do with idolatry is sheer idiocy. Somebody just brought me a pamphlet from England that he picked up in one of the tourism places, and it just says that a few hundred years ago there was a plague in England that begins as a rash on the hands shaped like a round rose etc. and the remedy was to put ash on it, and if you didn't you would fall down dead.

This prompts someone to post a link to Snopes where they debunk the story that "Ring Around the Rosie" has anything to do with any plague.

A heck of a journey, all told. From suspicious rumors of idolatry to widespread urban legends to Snopes. All within a week. This is the revolution the internet is causing in the Hasidic world - an instant acceleration to light speed. And we get to watch.

Friday, March 24, 2006

You Want I Should Grow A Beard?

One of my favorite Yiddishisms in English is the "I want you should" construction, a direct calque from Yiddish. I like it because it in part because it is so well-known, yet few know it's from Yiddish. My students always get a kick out of it (and yesterday they got a kick out of learning that "I don't have what to wear" is also a calque from Yiddish), and I get a kick out of hearing people use it, never suspecting it's a Yiddishism.

Through a roundabout series of events, I found myself reading the letter that inspired Abraham Lincoln to grow a beard -- you know the one, that an 11 year old girl (Grace Bedell from Westfield NY, not far from Erie PA) wrote -- and was struck by two things in the first two sentences:

On the other hand...

Googling "I want you should" reveals that this construction existed in English long before contact with Yiddish. Weird, no? Still, though, I'm convinced its current widespread use is due to Yiddish.

Through a roundabout series of events, I found myself reading the letter that inspired Abraham Lincoln to grow a beard -- you know the one, that an 11 year old girl (Grace Bedell from Westfield NY, not far from Erie PA) wrote -- and was struck by two things in the first two sentences:

My father has just home from the fair and brought home your picture and Mr. Hamlin's. I am a little girl only eleven years old, but want you should be President of the United States very much. (Italics mine)What is going on here? Are these archaisms? Mistakes? Most of the ghits for "has just home" refer to this letter, which leads me to suspect she accidentally left out the word "come" or "returned." Oddly enough, though, this too could be explained as a calque from Yiddish, if it weren't an absurd possibility.

On the other hand...

Googling "I want you should" reveals that this construction existed in English long before contact with Yiddish. Weird, no? Still, though, I'm convinced its current widespread use is due to Yiddish.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

A Slight Flaw

Commenter AJD raises an important cautionary note about the premise of my Unscientific Positive 'Anymore' Survey (UPAS), namely that many people who use positive 'anymore' insist they don't. I was aware of this fact in the back of my mind (I allude to it in my very first post), and while I think this adds to the unscientificness of my survey, it doesn't ruin it outright. Since I'm interested in finding where positive 'anymore' isn't, I don't really have another viable option than to flat-out ask people if they think it sounds reasonable, and take a 'no' as an indication that they don't use it, even though they might. What else am I going to do, an exhaustive corpus study? Please - that's for people who want meaningful results!

Anyways, the data is trickling in, so I've got that going for me, which is nice. While I'm typing, I wanted to mention a phenomenon I've only noticed in the last few years (not that that entails it's a recent phenomenon) that puzzles me slightly. Some people say things like "Since I am six years old" to mean "Ever since I was six years old," not "Because I am currently six years old." I feel like I've heard this both in Chicago and New York, and for a while I seemed to hear it only from African Americans, but then I heard it from non-African Americans too, but overall I haven't encountered it often enough to get a sense for its respective geographic, social and economic distribution. Is there a term for this? Has it been studied? Is it even noteworthy? I think it's interesting, especially since English is somewhat idiosyncratic when it comes to sequence of tense. In any case, I'd like to know more.

Anyways, the data is trickling in, so I've got that going for me, which is nice. While I'm typing, I wanted to mention a phenomenon I've only noticed in the last few years (not that that entails it's a recent phenomenon) that puzzles me slightly. Some people say things like "Since I am six years old" to mean "Ever since I was six years old," not "Because I am currently six years old." I feel like I've heard this both in Chicago and New York, and for a while I seemed to hear it only from African Americans, but then I heard it from non-African Americans too, but overall I haven't encountered it often enough to get a sense for its respective geographic, social and economic distribution. Is there a term for this? Has it been studied? Is it even noteworthy? I think it's interesting, especially since English is somewhat idiosyncratic when it comes to sequence of tense. In any case, I'd like to know more.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Positive Anymore 2: Revenge Of The Isogloss

If you don't know what positive 'anymore' means, you can read my description here or you can read something a bit more technical here. In fact, if you follow this last link, you will read

A while back I wrote about American words for 'soft drink', and I included a beautiful map based entirely on responses from an online survey. So this got me thinking: why can't I do the same thing for positive 'anymore'?

Here's where you come in. Tell me two things: 1) if you find the sentence "Gas sure is expensive anymore" shocking, or would have found it shocking at some point (not whether you've heard such sentences or if you use them) and 2) the zip code where you spent the biggest chunk of the first ten years of your life. Then bug your friends to do the same. I expect that in a few years I'll have enough thoroughly unscientific data to make an equally unscientific map. Maybe then I'll be able to sleep at night.

A confession:

I don't use positive 'anymore' natively. At least I don't think I do. I think that anymore I use it as an affectation of sorts, or as marked speech. But just because it isn't part of my dialect doesn't mean I can't love it.

The distribution of positive "anymore" is only vaguely geographic; mostly it's social dialects -- speech groups not necessarily distinguished by location -- that show it.This is true, for the most part, but I think there are nevertheless geographic limits, outside of which no one of any social group uses positive 'anymore'. The problem is, I don't really know where these limits are. Astute commenter and aspiring professional dialectologist Corrine/Queenie recently joked that the boundary ran through Chicago's western suburbs. Though she was joking, this may in fact be the case.

A while back I wrote about American words for 'soft drink', and I included a beautiful map based entirely on responses from an online survey. So this got me thinking: why can't I do the same thing for positive 'anymore'?

Here's where you come in. Tell me two things: 1) if you find the sentence "Gas sure is expensive anymore" shocking, or would have found it shocking at some point (not whether you've heard such sentences or if you use them) and 2) the zip code where you spent the biggest chunk of the first ten years of your life. Then bug your friends to do the same. I expect that in a few years I'll have enough thoroughly unscientific data to make an equally unscientific map. Maybe then I'll be able to sleep at night.

A confession:

I don't use positive 'anymore' natively. At least I don't think I do. I think that anymore I use it as an affectation of sorts, or as marked speech. But just because it isn't part of my dialect doesn't mean I can't love it.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

In The News

Well, now I have been mentioned on three of my favorite blogs: In Mol Araan, Langauge Log, and, as of yesterday, Language Hat. Pretty flattering, all told. Anyways, just wanted to brag.

What kind of responsible American dialectology blogger would I be if I didn't post on the latest round of publicity for William Labov's new groundbreaking (and still unseen by me) Atlas of North American English Phonetics, Phonology and Sound Change? This latest bout of media attention was spurred, as far as I can tell, by a NYT article in Friday's travel section, describing a dialectological roadtrip in which Tim Sultan heads northwest from New York City, in pursuit of dialectological diversity. Guided by the atlas and by Labov himself, Sultan drives towards Rochester, listening for evidence of the Northern cities vowel shift.

In interviews, Labov has been touting this vowel change as the most interesting ongoing development in American speech, and as evidence for his general yet counterintuitive theory about increasing diversification among American dialects. Labov often describes this vowel change, and the Inland Northern dialect that it typifies, as the "Chicago Dialect." As a Chicagoan, I was a bit surprised by this. Sure, I thought, Rochesterians may raise /ae/ and front /ah/, and they may not have the low-back merger, but that doesn't mean they sound like Chicagoans, does it?

Well, apparently it does. Perhaps you've encountered the gooey feel-good story that's been in the news recently about the autistic high-school basketball player making six 3-point shots in one game. I saw this CNN clip on the story, and when the coach started talking midway through, I thought, oh, they must be in the Chicago suburbs.

Of course, they're in Rochester. Go know. I must point out that this supports the theory I mentioned earlier about gym coaches tending to exhibit the local dialect.

Two postscripts: First off, notice the distinctly midland dialect of the CNN reporter. Growing up in the Inland North, I repeatedly heard that broadcasters tried to sound like they were from Michigan. This is based somewhat in reality - another version I heard was that there was conflict between those who favored Midland and those who favores Inland Northern. Given that Inland Northern is now changing, maybe Midland is ascendant again. If you want to hear good old Inland Northern broadcasters, though, check out Rochester's WROC news report on the same story.

Secondly, when we say "Chicago dialect," we generally mean the general dialect of the Chicagoland region. I still maintain that the dialect of the city itself is quite distinct from that of the suburbs. On the one hand, the stereotypical Chicago trait of /dis/ for "this" and so on, is not really found in the suburbs. Also, the vowel system in the city is a bit different; along with Rochester, Labov has been talking a lot about Pittsburg, giving as the shibboleth the monophthongized /dahntahn/ pronunciation of "downtown." There's a similar monophthongization in Chicago, though it's a bit further back, more like /donton/. These two traits, though certainly not unique to Chicago, make the dialect of the city distinct from general Inland Northern.

What kind of responsible American dialectology blogger would I be if I didn't post on the latest round of publicity for William Labov's new groundbreaking (and still unseen by me) Atlas of North American English Phonetics, Phonology and Sound Change? This latest bout of media attention was spurred, as far as I can tell, by a NYT article in Friday's travel section, describing a dialectological roadtrip in which Tim Sultan heads northwest from New York City, in pursuit of dialectological diversity. Guided by the atlas and by Labov himself, Sultan drives towards Rochester, listening for evidence of the Northern cities vowel shift.

In interviews, Labov has been touting this vowel change as the most interesting ongoing development in American speech, and as evidence for his general yet counterintuitive theory about increasing diversification among American dialects. Labov often describes this vowel change, and the Inland Northern dialect that it typifies, as the "Chicago Dialect." As a Chicagoan, I was a bit surprised by this. Sure, I thought, Rochesterians may raise /ae/ and front /ah/, and they may not have the low-back merger, but that doesn't mean they sound like Chicagoans, does it?

Well, apparently it does. Perhaps you've encountered the gooey feel-good story that's been in the news recently about the autistic high-school basketball player making six 3-point shots in one game. I saw this CNN clip on the story, and when the coach started talking midway through, I thought, oh, they must be in the Chicago suburbs.

Of course, they're in Rochester. Go know. I must point out that this supports the theory I mentioned earlier about gym coaches tending to exhibit the local dialect.

Two postscripts: First off, notice the distinctly midland dialect of the CNN reporter. Growing up in the Inland North, I repeatedly heard that broadcasters tried to sound like they were from Michigan. This is based somewhat in reality - another version I heard was that there was conflict between those who favored Midland and those who favores Inland Northern. Given that Inland Northern is now changing, maybe Midland is ascendant again. If you want to hear good old Inland Northern broadcasters, though, check out Rochester's WROC news report on the same story.

Secondly, when we say "Chicago dialect," we generally mean the general dialect of the Chicagoland region. I still maintain that the dialect of the city itself is quite distinct from that of the suburbs. On the one hand, the stereotypical Chicago trait of /dis/ for "this" and so on, is not really found in the suburbs. Also, the vowel system in the city is a bit different; along with Rochester, Labov has been talking a lot about Pittsburg, giving as the shibboleth the monophthongized /dahntahn/ pronunciation of "downtown." There's a similar monophthongization in Chicago, though it's a bit further back, more like /donton/. These two traits, though certainly not unique to Chicago, make the dialect of the city distinct from general Inland Northern.

Friday, March 17, 2006

American Insecurity

I have a lot of friends and colleagues who aren't native English speakers. All of them have accents, which is no surprise; the few people I have met who speak English without an accent but learned it as adults weren't able to do so by virtue of their intelligence, but because, frankly, they are freaks; their talent, I think, is akin to being able to multiply large numbers instantly or having a photographic memory. In short, there is no shame in having an accent. It is therefore surprising that

1) Non-native speakers are ashamed of their accents when they speak English, and

2) Americans are ashamed of their accents when they speak other languages.

On the face of it, these two facts seems to be one and the same, but, I believe, they are distinct. How so? Well, recently I had the same conversation on two occasions with two different people, both of whom spoke fine English, albeit with accents. They each pressed me to give minute feedback on their English, because they were mortified at the thought of sounding non-native. I assured them that when Americans hear someone speaking with an accent, their instinctive response is to be impressed, not just at the ability of foreigners to speak English, but with their very foreignness. So when foreigners are embarrassed about their accents, they are fundamentally misunderstanding how they are perceived. Why do they do so? Well, the answer is related to why Americans are embarrassed about their own accents. When we Americans trot out our Spanish, French or Mandarin, and cringe at our own accents, we know we are not the only ones cringing; so too are our interlucutors. Not everyone is impressed by a foreign accent. Indeed, I think Americans, while perhaps not unique in this regard, are certainly exceptional in our overall positive attitude towards accents. This positivity can be explained several ways. On the one hand, Americans have long had experience with immigration and large-scale language acquisition, something the rest of the world has not experienced to the same extent for the same amount of time. But I think the primary reason is that we just have a deep-seated insecurity about our own language and culture. When we hear an accent - any accent, I will posit - we think, aha! This is someone from a real place who speaks a real language.

I must admit that I too have the same instinctive reactions; when I hear an accent, I feel distinctly impressed, and when I speak French or Yiddish, I am ashamed of my own (and others') American accent, as well as that of others'. And it goes even deeper; when I hear any foreign accent in Yiddish (the only language other than English that I know well) I have the same negative reaction, be it a Hebrew, Russian, or German accent. In a way, then, when I cease being an Anglophone, I lose my anglophonic openness. Ultimately, though, I know that both my positive and negative feelings about accents are misplaced; an accent should be a neutral thing. And yet it isn't.

I have been thinking about this for most of my life, but not systematically, and there are a number of unresolved issues I wish I knew more about. Firstly, if Americans are not unique in our prejudice in favor of accents, who else shares this prejudice? Secondly, is it that non-Anglophones particularly dislike American accents, or are they equally offended by, say, French or Russian accents? And finally, I do think that Americans' positive impression of non-native speakers is not limited to Europeans; I think we are just as impressed by a Yoruba accent or a Japanese accent as we are by an Italian one. But are there limits? My instinct on this is that we are less impressed by Spanish accents and perhaps strong Chinese accents. If anyone has thoughts about these questions, please let me know.

1) Non-native speakers are ashamed of their accents when they speak English, and

2) Americans are ashamed of their accents when they speak other languages.

On the face of it, these two facts seems to be one and the same, but, I believe, they are distinct. How so? Well, recently I had the same conversation on two occasions with two different people, both of whom spoke fine English, albeit with accents. They each pressed me to give minute feedback on their English, because they were mortified at the thought of sounding non-native. I assured them that when Americans hear someone speaking with an accent, their instinctive response is to be impressed, not just at the ability of foreigners to speak English, but with their very foreignness. So when foreigners are embarrassed about their accents, they are fundamentally misunderstanding how they are perceived. Why do they do so? Well, the answer is related to why Americans are embarrassed about their own accents. When we Americans trot out our Spanish, French or Mandarin, and cringe at our own accents, we know we are not the only ones cringing; so too are our interlucutors. Not everyone is impressed by a foreign accent. Indeed, I think Americans, while perhaps not unique in this regard, are certainly exceptional in our overall positive attitude towards accents. This positivity can be explained several ways. On the one hand, Americans have long had experience with immigration and large-scale language acquisition, something the rest of the world has not experienced to the same extent for the same amount of time. But I think the primary reason is that we just have a deep-seated insecurity about our own language and culture. When we hear an accent - any accent, I will posit - we think, aha! This is someone from a real place who speaks a real language.

I must admit that I too have the same instinctive reactions; when I hear an accent, I feel distinctly impressed, and when I speak French or Yiddish, I am ashamed of my own (and others') American accent, as well as that of others'. And it goes even deeper; when I hear any foreign accent in Yiddish (the only language other than English that I know well) I have the same negative reaction, be it a Hebrew, Russian, or German accent. In a way, then, when I cease being an Anglophone, I lose my anglophonic openness. Ultimately, though, I know that both my positive and negative feelings about accents are misplaced; an accent should be a neutral thing. And yet it isn't.

I have been thinking about this for most of my life, but not systematically, and there are a number of unresolved issues I wish I knew more about. Firstly, if Americans are not unique in our prejudice in favor of accents, who else shares this prejudice? Secondly, is it that non-Anglophones particularly dislike American accents, or are they equally offended by, say, French or Russian accents? And finally, I do think that Americans' positive impression of non-native speakers is not limited to Europeans; I think we are just as impressed by a Yoruba accent or a Japanese accent as we are by an Italian one. But are there limits? My instinct on this is that we are less impressed by Spanish accents and perhaps strong Chinese accents. If anyone has thoughts about these questions, please let me know.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

לכּבֿד פּורים - In Honor Of Purim

Today is Purim, and tomorrow isn't, so I thought I'd post on a Purim-related theme: intoxication. See, Purim, the festival commemorating the events of the Book of Esther, is particularly associated with drunkenness, all thanks to a throwaway line in the Talmud, saying,

As for Yiddish, intoxication and folk etymologies, one of my students shared with me his deeply held but erroneous belief that the term 'crunk' is from Yiddish קראַנק /krank/ "sick." I hated to burst his bubble on that one, but fortunately for him he didn't believe me.

A man is obliged to intoxicate himself on Purim, till he cannot distinguish between "cursed be Haman" and "blessed be Mordecai." (BT Megillah 7b)Now so much attention has been paid to this line that the passage that follows has been all but ignored. So I'll quote it for posterity:

Yeah, I think I'd turn down that invitation too. But regardless, my goal here is to pass along an interesting fact I learned in a blog I just found, Balashon, where I learned that the Hebrew word for drunk, שיכּור, (which, oddly enough, is not the word used in the passage above - more on this also at Balashon), which gave rise to the Jewish English word 'shiker' via Yiddish, is cognate, through a complicated route, with the English word 'cider.' Now that's cool. It sounds like a folk etymology, I know, but the OED backs it up.Rabbah and Rav Zeira celebrated the Purim feast together. They became intoxicated. Rabbah stood up and killed Rav Zeira. The next day, he prayed for mercy and brought him back to life.

The following year, [Rabbah] again invited [Rav Zeira] to celebrate the feast together. Rav Zeira answered, "A miracle does not happen all the time."

As for Yiddish, intoxication and folk etymologies, one of my students shared with me his deeply held but erroneous belief that the term 'crunk' is from Yiddish קראַנק /krank/ "sick." I hated to burst his bubble on that one, but fortunately for him he didn't believe me.

Sunday, March 12, 2006

The Weird, Wild Hasidic World

If you haven't heard, there is a new movie out called A Gesheft - "A Deal." Oh yeah, and it's in Yiddish.

This movie was produced on the fringes of the insular world of Hasidic Jews, intended for consumption within that community. Even though the movie goes to great lengths to be pious, it has attracted a fair amount of negative attention -- not only were adds placed in two major Hasidic newspapers denouncing the movie (not for its content, but for being a movie), but moreover my informants tell me no one in the Hasidic community is admitting watching it.

Well, not being Hasidic, I had no problem seeing it. It was good, and though far from slick it was a lot more professional than I had expected; it was professionally edited, and as it turns out I know the editor slightly -- the world of Yiddish enthusiasts is not vast. In a way, the existence this movie shows that Hasidic culture is in more contact with the outside world than is generally presumed. One aspect of the movie, though, mitigates this; the main action of the movie takes place in the present, but there are several extended flashback sequences, one of which, onscreen titles inform us, takes place forty years ago. In this sequence, not only are there a number of conspicuous technological items that did not exist forty years ago, but a key plot element involves a fancy-looking computer with a flatscreen color monitor. To me this suggests not ignorance on the part of the people making the movie; who doesn't know, especially in the increasingly wired Hasidic world, that there weren't flatscreen color monitors in the past? No, this is due, rather, to a willingness to disregard historical context that is unthinkable in non-Hasidic American culture.

I was told about this scene before I saw the movie, so it wasn't exactly a surprise, but seeing it in context was still shocking to me, given the general competence of the movie-making. I had expected a much more homemade film, in which blatant anachronisms are par for the proverbial course.

On a related note, the Yiddish edition of Wikipedia has changed radically over the last few months. A lot of work has gone into it, and I'm particularly fond of the news headlines on the first page, which are charmingly gossipy. Still, though, there are vestiges of the old Yiddish Wikipedia; several months ago I posted about a Hasidic blog I loved for its (perhaps inadvertent) quirkiness. Soon this blogger quit blogging and devoted his attention to Wikipedia. Thanks to him, if for some reason you wished to read the Yiddish Wikipedia article on shoes, you would find out,

Speaking of the Yiddish Wikipedia, through its news section I found an article in the Forverts, the oldest Yiddish newspaper, that mentioned a paper I gave at a conference recently. Pretty cool, eh?

This movie was produced on the fringes of the insular world of Hasidic Jews, intended for consumption within that community. Even though the movie goes to great lengths to be pious, it has attracted a fair amount of negative attention -- not only were adds placed in two major Hasidic newspapers denouncing the movie (not for its content, but for being a movie), but moreover my informants tell me no one in the Hasidic community is admitting watching it.

Well, not being Hasidic, I had no problem seeing it. It was good, and though far from slick it was a lot more professional than I had expected; it was professionally edited, and as it turns out I know the editor slightly -- the world of Yiddish enthusiasts is not vast. In a way, the existence this movie shows that Hasidic culture is in more contact with the outside world than is generally presumed. One aspect of the movie, though, mitigates this; the main action of the movie takes place in the present, but there are several extended flashback sequences, one of which, onscreen titles inform us, takes place forty years ago. In this sequence, not only are there a number of conspicuous technological items that did not exist forty years ago, but a key plot element involves a fancy-looking computer with a flatscreen color monitor. To me this suggests not ignorance on the part of the people making the movie; who doesn't know, especially in the increasingly wired Hasidic world, that there weren't flatscreen color monitors in the past? No, this is due, rather, to a willingness to disregard historical context that is unthinkable in non-Hasidic American culture.

I was told about this scene before I saw the movie, so it wasn't exactly a surprise, but seeing it in context was still shocking to me, given the general competence of the movie-making. I had expected a much more homemade film, in which blatant anachronisms are par for the proverbial course.

On a related note, the Yiddish edition of Wikipedia has changed radically over the last few months. A lot of work has gone into it, and I'm particularly fond of the news headlines on the first page, which are charmingly gossipy. Still, though, there are vestiges of the old Yiddish Wikipedia; several months ago I posted about a Hasidic blog I loved for its (perhaps inadvertent) quirkiness. Soon this blogger quit blogging and devoted his attention to Wikipedia. Thanks to him, if for some reason you wished to read the Yiddish Wikipedia article on shoes, you would find out,

With shoes you can walk on glass and stones without any pain or injury, shoelaces keep them tight and help you walk without any problems.I don't wish to mock this; my point is to show that inspite of the considerable contact Hasidim have nowadays with the outside world, there are still people who are sufficiently unfamiliar with encyclopedias that they think this is a reasonable article. In a way, that's a beautiful thing.

Speaking of the Yiddish Wikipedia, through its news section I found an article in the Forverts, the oldest Yiddish newspaper, that mentioned a paper I gave at a conference recently. Pretty cool, eh?

Friday, March 10, 2006

Carl Schurz is Alright

I don't know why I never knew this, but it turns out that the cover photo of the Who's album "The Kids Are Alright," and album I have owned since childhood, was taken in my neighborhood. Today was unseasonably warm (though not exactly nice) so I went for a walk and verified it myself.

Here's the album cover:

And here's a picture I took of the same spot: No doubt about it, it's the same spot, though why they (or rather Art Kane, the photographer) picked this place I don't know. It's a nice spot, with a great view of Harlem, and a stone bench that radiates heat on a sunny day.

No doubt about it, it's the same spot, though why they (or rather Art Kane, the photographer) picked this place I don't know. It's a nice spot, with a great view of Harlem, and a stone bench that radiates heat on a sunny day.

Apparently, there is a widely held belief that the album cover was taken at Grant's Tomb. It isn't, although, Grant's Tomb is about a ten minute walk away. In fact, this frieze is part of a monument to Carl Schurz, a German immigrant who became famous first as a Union general in the Civil War, and later as a progressive politician.

To me he is most noteworthy for being the namesake of a public high school in Chicago. Designed by Dwight Perkins in 1908, it is a masterpiece of Prairie School architecture, as the following images should demonstrate:

Lesser known is that the same year Perkins designed an extremely similar Chicago high school on the south side - Bowen High School, my father's alma mater. You can see that it is a wonderful building as well, though ill-advised renovations have diminished its charm.

Here's the album cover:

And here's a picture I took of the same spot:

No doubt about it, it's the same spot, though why they (or rather Art Kane, the photographer) picked this place I don't know. It's a nice spot, with a great view of Harlem, and a stone bench that radiates heat on a sunny day.

No doubt about it, it's the same spot, though why they (or rather Art Kane, the photographer) picked this place I don't know. It's a nice spot, with a great view of Harlem, and a stone bench that radiates heat on a sunny day.Apparently, there is a widely held belief that the album cover was taken at Grant's Tomb. It isn't, although, Grant's Tomb is about a ten minute walk away. In fact, this frieze is part of a monument to Carl Schurz, a German immigrant who became famous first as a Union general in the Civil War, and later as a progressive politician.

To me he is most noteworthy for being the namesake of a public high school in Chicago. Designed by Dwight Perkins in 1908, it is a masterpiece of Prairie School architecture, as the following images should demonstrate:

Lesser known is that the same year Perkins designed an extremely similar Chicago high school on the south side - Bowen High School, my father's alma mater. You can see that it is a wonderful building as well, though ill-advised renovations have diminished its charm.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

Just to Confirm

I think of myself as somewhat savvy, having grown up on the mean streets of Chicago's South Side. Well, okay, the streets weren't so mean in my neighborhood, but you get my point: it's not easy to pull one over on me. And yet I recently fell victim to a very small scam of sorts, which was easy enough to extricate myself from; I got enrolled in a stupid "credit protection" program I hadn't intended to become enrolled in, and it only took one phone call to get me out. But as the president says, if fool me can't get fooled again. So when I got a call the other day with the same scamlet (something is rotten in a call center in India) I heard them out just to see how it was that they fooled me before. Though I am not a semanticist, or even a linguist, I feel that the mechanism of the scam poses interesting implicature problems. Here's how it works:

1. They call and explain the program in rapid, excruciating detail.

2. They explain that you can read all about the excruciating details because they will send you information after you enroll.

3. They say that in order to send you that information they need to verify your address. Then they read you your address and ask if it is correct. If you say yes, congratulations! You are now paying $9.95 a month for a useless service.

The reason this is aboveboard is that the people running this think that by confirming your address, you are implying consent for enrollment. How's that? Simple; you are confirming your address so they can send you the information. Aha, but they already said that they send you the information once you enroll. If you confirm your address, it means you want them to send the information, which means you must want to enroll.

But I don't buy it. Somehow I feel like a step is missing, and that at some level, despite the reasoning I just layed out, confirming your address is not the same as saying you want them to send the information. I'm not even sure saying you want the information entails you want to enroll.

There are a few other odd quirks about how they go about doing this, most of which I think are designed to confuse and to keep you from figuring out the dubious logic behind your scam. First of all, it's one of those cases where the call center is clearly in India, but they use a fake "American" name; my caller called himself "John Adams," which I found amusing. But often these people using fake American names are also faking an American accent, and doing a halfway decent job. Not my John Adams, who made no effort to sound like a John Adams. In fact, his accent and the speed of his delivery combined to make him somewhat hard to understand. But the real trick (and this happenned both times) was that, right before reading my address, the callers took on a very humble and apologetic tone: "Sir, I have to read you your address now. It's part of my job." At this point, if you aren't already confused, you will be, and you'll even feel obligated to have your address read to you. He has to read it. It's part of his job. I certainly don't want John Adams to get fired on my account.

I write this not as a warning, but because I think it's interesting, especially because it's a major bank that has undoubtedly concocted this scheme with the intention of fooling people into agreeing to something they don't intend to. But what is most interesting is that the argument form is, I think, invalid. They aren't fooling us into agreeing. They're fooling themselves.

1. They call and explain the program in rapid, excruciating detail.

2. They explain that you can read all about the excruciating details because they will send you information after you enroll.

3. They say that in order to send you that information they need to verify your address. Then they read you your address and ask if it is correct. If you say yes, congratulations! You are now paying $9.95 a month for a useless service.

The reason this is aboveboard is that the people running this think that by confirming your address, you are implying consent for enrollment. How's that? Simple; you are confirming your address so they can send you the information. Aha, but they already said that they send you the information once you enroll. If you confirm your address, it means you want them to send the information, which means you must want to enroll.

But I don't buy it. Somehow I feel like a step is missing, and that at some level, despite the reasoning I just layed out, confirming your address is not the same as saying you want them to send the information. I'm not even sure saying you want the information entails you want to enroll.

There are a few other odd quirks about how they go about doing this, most of which I think are designed to confuse and to keep you from figuring out the dubious logic behind your scam. First of all, it's one of those cases where the call center is clearly in India, but they use a fake "American" name; my caller called himself "John Adams," which I found amusing. But often these people using fake American names are also faking an American accent, and doing a halfway decent job. Not my John Adams, who made no effort to sound like a John Adams. In fact, his accent and the speed of his delivery combined to make him somewhat hard to understand. But the real trick (and this happenned both times) was that, right before reading my address, the callers took on a very humble and apologetic tone: "Sir, I have to read you your address now. It's part of my job." At this point, if you aren't already confused, you will be, and you'll even feel obligated to have your address read to you. He has to read it. It's part of his job. I certainly don't want John Adams to get fired on my account.

I write this not as a warning, but because I think it's interesting, especially because it's a major bank that has undoubtedly concocted this scheme with the intention of fooling people into agreeing to something they don't intend to. But what is most interesting is that the argument form is, I think, invalid. They aren't fooling us into agreeing. They're fooling themselves.

Monday, March 06, 2006

An African Dialect

On NPR this morning they reported that while accepting an award at last night's Oscars, director Gavin Hood addressed the stars of his movie "Tsotsi" in "an African dialect." Hearing this, I realized that there is a meaning of the word 'dialect' that is confined largely to the media. Instead of meaning "a variety of a language," in this instance I think dialect means "a language whose identity we were unwilling to determine." See, if they said "he addressed the stars of the movie in an African language," they would sound ignorant, right? But if they say dialect, suddenly they seem to be very knowing -- oh that, that's just a dialect there.

I think that this happens especially often with Africa, for a number of reasons. First of all, nations correspond extremely poorly to indigenous languages on that continent, as opposed to Asia and Europe, where they merely correspond poorly. Thus if a German director had said something in some foreign language, it wouldn't be too hard to figure out what language he or she was speaking, or if Ang Lee said something in some other funny language (which he did) you can fairly certainly ascertain from the fact that he is from Taiwan that he was speaking Thai. Yes, II'm kidding. But if a South Africa says something foreign, all bets are off. An African dialect.

Another factor is that I think most Americans think of Africa as a fairly homogenous place, so that it's hard to pin down anything specific there. Sweden is Sweden and Italy is Italy, and though I think the differences between China and Japan are quite subtle (kidding again), most people are aware that differences exist. But Botswana? Nigeria? Tanzania? Who knows? An African dialect.

Finally, I think there is a lingering colonialist attitude, in spite of the progress of the last century, that makes people think of Africa as a primitive place, where maybe they don't even speak real languages. Languages are spoken in places where there are cathedrals, or maybe pagodas. An African dialect.

Okay, maybe I'm a bit too harsh in my judgement. There was a street slang in South Africa's Gauteng province called Tsotsitaal (the film's title "Tsotsi" means criminal in Arikaans, and Tsotsitaal meansRed Welsh 'criminalese'), which has developed into a modern version called isiCamtho. Wikipedia says it is a pidgin based on Zulu, Xhosa, Tswan, English and Afrikaans (which seems a bit vague to me). I guess in this case NPR was only somewhat lazy in calling this "an African dialect," if indeed this is what Hood was speaking. But I still think I'm on to something here.

I think that this happens especially often with Africa, for a number of reasons. First of all, nations correspond extremely poorly to indigenous languages on that continent, as opposed to Asia and Europe, where they merely correspond poorly. Thus if a German director had said something in some foreign language, it wouldn't be too hard to figure out what language he or she was speaking, or if Ang Lee said something in some other funny language (which he did) you can fairly certainly ascertain from the fact that he is from Taiwan that he was speaking Thai. Yes, II'm kidding. But if a South Africa says something foreign, all bets are off. An African dialect.

Another factor is that I think most Americans think of Africa as a fairly homogenous place, so that it's hard to pin down anything specific there. Sweden is Sweden and Italy is Italy, and though I think the differences between China and Japan are quite subtle (kidding again), most people are aware that differences exist. But Botswana? Nigeria? Tanzania? Who knows? An African dialect.

Finally, I think there is a lingering colonialist attitude, in spite of the progress of the last century, that makes people think of Africa as a primitive place, where maybe they don't even speak real languages. Languages are spoken in places where there are cathedrals, or maybe pagodas. An African dialect.

Okay, maybe I'm a bit too harsh in my judgement. There was a street slang in South Africa's Gauteng province called Tsotsitaal (the film's title "Tsotsi" means criminal in Arikaans, and Tsotsitaal means

Even if it is broke...

don't fix it. That's my philosophy. At least when it comes to complex, arbitrary sets of conventions. You know, like grammar, or spelling. And by "don't fix it" I mean "don't try to make it conform to your own 'logical' principles, because human language ain't logical, my friend." Gee, who knew the voice in my head could sound so folksy?

What got me on this track was a recent allusion in Language Log to Theodore Roosevelt's attempt at spelling reform: apparently, Roosevelt took a list of 300 spelling changes devised by Andrew Carnegie's Simplified Spelling Board and ordered the Government Printing Office to start using the new spellings. This caused a public outcry (but not as big as if this were to happen today, I bet). Ultimately congress passed a resolution condemning the order, and Roosevelt withdrew it.

I'd never heard of this before, and was curious to see what the changes were. I've so far only been able to find sample lists, though as of 2002 an organization called the American Literacy Council was selling copies of the list for $5.

Now, I can't fault the impulses behind spelling reform; Roosevelt, Carnegie et al. were driven by progressive, populist sentiments which I endorse wholeheartedly. Furthermore, while I am a good speller (but a poor copyeditor, as regular readers are no doubt aware) I sympathize with those frustrated by English's complex spelling. And I think that the backlash against spelling reform was driven by smugness and snobbery, which I definitely don't approve of. No, my beef with spelling reform is that it is simply taking one illogical system and replacing it with another one, but one that no one knows. This just happened in Germany, and there has been no real benefit; German spelling is no easier, and now those who used to know how to spell in German no longer do.

Yiddish has had a disproportionate number of brushes with spelling reform; the Soviets reformed Yiddish spelling three times, and a consortium of academics invented their own spelling system in 1937, which to this day is considered 'standard' in academic settings, even though only a tiny fraction of Yiddish texts since 1937 have used this system, which is in fact more complex than the conventional Yiddish spelling. I use 'standard' spelling in my class, and I feel guilty knowing that if and when any of my students goes on to read Yiddish on their own they will see the rules I taught them flaunted.

Which reminds me; I meant to have a footnote in my last post about the verb 'to flaunt' which can mean either "to exhibit ostentatiously" or "to disobey (ostentatiously?)." The latter came about through confusion with "flout" and some consider it nonstandard, but the OED cites Noel Coward using it in 1938, which makes it kosher in my book.

What got me on this track was a recent allusion in Language Log to Theodore Roosevelt's attempt at spelling reform: apparently, Roosevelt took a list of 300 spelling changes devised by Andrew Carnegie's Simplified Spelling Board and ordered the Government Printing Office to start using the new spellings. This caused a public outcry (but not as big as if this were to happen today, I bet). Ultimately congress passed a resolution condemning the order, and Roosevelt withdrew it.

I'd never heard of this before, and was curious to see what the changes were. I've so far only been able to find sample lists, though as of 2002 an organization called the American Literacy Council was selling copies of the list for $5.

Now, I can't fault the impulses behind spelling reform; Roosevelt, Carnegie et al. were driven by progressive, populist sentiments which I endorse wholeheartedly. Furthermore, while I am a good speller (but a poor copyeditor, as regular readers are no doubt aware) I sympathize with those frustrated by English's complex spelling. And I think that the backlash against spelling reform was driven by smugness and snobbery, which I definitely don't approve of. No, my beef with spelling reform is that it is simply taking one illogical system and replacing it with another one, but one that no one knows. This just happened in Germany, and there has been no real benefit; German spelling is no easier, and now those who used to know how to spell in German no longer do.

Yiddish has had a disproportionate number of brushes with spelling reform; the Soviets reformed Yiddish spelling three times, and a consortium of academics invented their own spelling system in 1937, which to this day is considered 'standard' in academic settings, even though only a tiny fraction of Yiddish texts since 1937 have used this system, which is in fact more complex than the conventional Yiddish spelling. I use 'standard' spelling in my class, and I feel guilty knowing that if and when any of my students goes on to read Yiddish on their own they will see the rules I taught them flaunted.

Which reminds me; I meant to have a footnote in my last post about the verb 'to flaunt' which can mean either "to exhibit ostentatiously" or "to disobey (ostentatiously?)." The latter came about through confusion with "flout" and some consider it nonstandard, but the OED cites Noel Coward using it in 1938, which makes it kosher in my book.

Friday, March 03, 2006

Don't Believe The 'ype

As a little kid two of my main obsessions were music and accents (plus ça change...) and I remember watching "Yellow Submarine" when I was about five and thinking to myself how odd it was that the Beatles spoke with British accents but sang with American ones. Only years later did I realize that this initial impression wasn't entirely accurate.

In fact, the Beatles sing with what I call "Standard English Singing Pronunciation," which is a standard shared by most Anglophones, including Americans. Its salient (or perhaps typifying) feature is that it is non-rhotic. Indeed, just about the only popular American music that is rhotic is country music.

Now this is an odd situation, and it merits some consideration. There may be research on the topic, but since this isn't my field I don't need to know about it. Although an alarmingly high percentage of my readers are linguists, especially now after Ben Zimmer mentioned me in a post on Language Log, so I should perhaps think twice before flaunting my ignorance. Except ignorance is so fun to flaunt.*

In short, the situation is not that the Beatles sing with American pronunciation, but that Americans sing with British pronunciation, more or less. And yes, I know that there are rhotic British dialects and non-rhotic American ones. In fact, the latter will come to play in my made-up explanation. Firstly, though, it is well known from early recordings that for public occasions Americans (or at least Americans from a certain background) would adopt a very strange non-rhotic accent. It could be that singing, as a kind of public performance, also had this "fancy" pronunciation in America in some contexts. Perhaps then this became a convention that is retained to this day as a hallmark of musicality. On the other hand, not all music lends itself to conventions associated with prestige and formality; I think that in these cases (non-black) Americans sing non-rhotically in partial imitation of African American vernacular, which has, of course, had a profound effect on all American music. Thus non-rhotic singing has associations that are both formal and not formal. I think that now we are closer to understanding why country music, alone among styles of American music, adopted rhotic pronunciation, despite the number of country singers from the South, a region where there is fairly widespread derhotacization: in order to project an image of folksiness, country singers couldn't use a fancy non-rhotac pronunciation, nor were they eager, as white Southerners, to co-opt a hallmark of African American pronunciations. Indeed, the most famous African American country singer, Charley Pride, sings with a markedly rhotic pronunciation, even though he's from the Mississippi delta, where African Americans (but not whites) derhotacize.

On the other hand, a large number of Country singers are from fully rhotic Texas, and this is probably a factor too, as is the fact that the center of the industry is in rhotic Nashville. Hank Williams presents an interesting case; he is from southern Alabama and he sings with a strong rhotic pronunciation. According to a map on Wikipedia, which is based on Labov et al., the isogloss runs right through this area. I haven't been able to find any recording of Williams spekaing, though I'm sure they exist; it would be interesting to know whether he had a rhotic pronunciation or not.

So when, as a kid, I identified the Beatles' singing pronunciation as American, I wasn't entirely off the map. I believe I was also noticing the contrast between their Liverpudlian "Scouse" dialect and there more generic singing pronunciation. It seems that increasingly, though, U.K. musicians are starting to use distinctly local pronunciations. One prominent example is the "it" band of the moment, the Arctic Monkeys, from Sheffield, Yorkshire. So far they are following a now all-too-familiar pattern with British pop musicians: intense media hype followed by a nasty critical backlash in the equally nasty British music press. Others attack them for using too many localisms in their singing, which I think is sad. I must say, though, I don't really hear that many localisms, though I haven't listened to enough of their music to judge; I haven't heard them sing "tha" (thou) for instance, one of my favorite Yorkshire features, but I did catch an "owt" (something/anything). Here's a video of a live performance, and you can hear their dialect for yourself, although it is markedly less strong when they sing than the spoken bit at the beginning, my favorite part of which is when, in reference to all the flap in the press about them, the lead singer says "Don't believe the 'ype," pronouncing "the" as /ði/.

Speaking of videos, British musicians and their dialects, and backlash against heavily hyped bands, check out the following clip of the Beatles performing a very silly skit on a British T.V. show, I'm guessing in 1963. Notice their exaggerated Scouse dialect, but notice too the reaction of the crowd. In addition to the de rigueur screaming, there is a considerable amount of heckling, most of which consists of "shut up" and "go back to Liverpool." In a way it's comforting to think that even the Beatles had to face hecklers.

In fact, the Beatles sing with what I call "Standard English Singing Pronunciation," which is a standard shared by most Anglophones, including Americans. Its salient (or perhaps typifying) feature is that it is non-rhotic. Indeed, just about the only popular American music that is rhotic is country music.

Now this is an odd situation, and it merits some consideration. There may be research on the topic, but since this isn't my field I don't need to know about it. Although an alarmingly high percentage of my readers are linguists, especially now after Ben Zimmer mentioned me in a post on Language Log, so I should perhaps think twice before flaunting my ignorance. Except ignorance is so fun to flaunt.*

In short, the situation is not that the Beatles sing with American pronunciation, but that Americans sing with British pronunciation, more or less. And yes, I know that there are rhotic British dialects and non-rhotic American ones. In fact, the latter will come to play in my made-up explanation. Firstly, though, it is well known from early recordings that for public occasions Americans (or at least Americans from a certain background) would adopt a very strange non-rhotic accent. It could be that singing, as a kind of public performance, also had this "fancy" pronunciation in America in some contexts. Perhaps then this became a convention that is retained to this day as a hallmark of musicality. On the other hand, not all music lends itself to conventions associated with prestige and formality; I think that in these cases (non-black) Americans sing non-rhotically in partial imitation of African American vernacular, which has, of course, had a profound effect on all American music. Thus non-rhotic singing has associations that are both formal and not formal. I think that now we are closer to understanding why country music, alone among styles of American music, adopted rhotic pronunciation, despite the number of country singers from the South, a region where there is fairly widespread derhotacization: in order to project an image of folksiness, country singers couldn't use a fancy non-rhotac pronunciation, nor were they eager, as white Southerners, to co-opt a hallmark of African American pronunciations. Indeed, the most famous African American country singer, Charley Pride, sings with a markedly rhotic pronunciation, even though he's from the Mississippi delta, where African Americans (but not whites) derhotacize.

On the other hand, a large number of Country singers are from fully rhotic Texas, and this is probably a factor too, as is the fact that the center of the industry is in rhotic Nashville. Hank Williams presents an interesting case; he is from southern Alabama and he sings with a strong rhotic pronunciation. According to a map on Wikipedia, which is based on Labov et al., the isogloss runs right through this area. I haven't been able to find any recording of Williams spekaing, though I'm sure they exist; it would be interesting to know whether he had a rhotic pronunciation or not.

So when, as a kid, I identified the Beatles' singing pronunciation as American, I wasn't entirely off the map. I believe I was also noticing the contrast between their Liverpudlian "Scouse" dialect and there more generic singing pronunciation. It seems that increasingly, though, U.K. musicians are starting to use distinctly local pronunciations. One prominent example is the "it" band of the moment, the Arctic Monkeys, from Sheffield, Yorkshire. So far they are following a now all-too-familiar pattern with British pop musicians: intense media hype followed by a nasty critical backlash in the equally nasty British music press. Others attack them for using too many localisms in their singing, which I think is sad. I must say, though, I don't really hear that many localisms, though I haven't listened to enough of their music to judge; I haven't heard them sing "tha" (thou) for instance, one of my favorite Yorkshire features, but I did catch an "owt" (something/anything). Here's a video of a live performance, and you can hear their dialect for yourself, although it is markedly less strong when they sing than the spoken bit at the beginning, my favorite part of which is when, in reference to all the flap in the press about them, the lead singer says "Don't believe the 'ype," pronouncing "the" as /ði/.

Speaking of videos, British musicians and their dialects, and backlash against heavily hyped bands, check out the following clip of the Beatles performing a very silly skit on a British T.V. show, I'm guessing in 1963. Notice their exaggerated Scouse dialect, but notice too the reaction of the crowd. In addition to the de rigueur screaming, there is a considerable amount of heckling, most of which consists of "shut up" and "go back to Liverpool." In a way it's comforting to think that even the Beatles had to face hecklers.

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)