There's a saying in Yiddish that is based on a Talmudic aphorism: "A word to the wise is enough."

Sound familiar? That's because Benjamin Franklin said the same thing, most famously in his 1758 essay "The Way to Wealth," an essay which is basically a compendium of Poor Richard's sayings strung together. This implies that there is an earlier instance of the phrase in the Franklin corpus, but I don't feel like doing the research to find it.

So does this mean that Benjamin Franklin read the Talmud? Of course not. It doesn't even imply that his use of the phrase has any connection to the Talmud. A clever phrase like that can be invented multiple times, because people are clever. Almost makes you believe in universal human nature, don't it?

I tried to find the Talmudic instance of the phrase and failed, which I don't feel too bad about; after all, the Talmud is traditionally compared to the sea, meaning basically that it is huge. In my search I employed a clever technique, which, though ultimately unsuccesful, led me on an interesting journey, the highlights of which I will now share.

My clue in this search was a bit of information given to me by me colleague Naomi Kadar - "Whoever passes on a teaching in the name of the person who said it brings freedom to the world" - Pirke Avot 6:6. (Ironically, this saying isn't attributed.) She said that the maxim in full is "A word to the wise is sufficient, but for a fool not even a stick helps," and that the word for stick is קונדס, which has come to mean "prankster" in Yiddish. One of the two rival American Yiddish humor magazines in the early twentieth century was called דער גרױסער קונדס, "The Big Prankster," but the English title on the masthead was "The Big Stick," which I always found puzzling, but which this bit of information clarified.

So using this information, I went to Jastrow - that is, to Marcus Jastrow's legendary

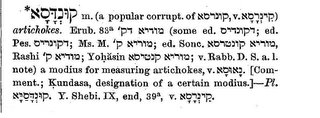

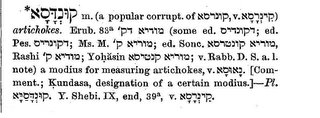

Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, hoping to get what is known in the yeshiva as a Jastrow Double - a citation of the very passage that sent you to the damn dictionary in the first place. No luck. I learned, not surprisingly, that this is one of many words of Talmudic Aramaic that are not Semitic in origin, which you can tell from the word itself. It comes from the Greek κοντός, which refers to a cavalry lance used particularly on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Cognates exist in Latin, Hungarian, Turkish and Arabic. All of Jastrow's citations, however, seemed to have to do not with lances, but with poles, and specifically poles used to hold things up, such as wedding canopies and eruvin (boundaries used to turn large areas into "homes," within which the Sabbath restriction on carrying is looser) and in one instance some unfortunate individual's head and hands. It seemed a little odd, though not impossible, that the sense would be so different in the Talmud, but then I remembered that Naomi said that the form of the word was קונדסא, which made sense, since in Aramaic a א at the end of a word is often a definite article. Jastrow does indeed have the word קונדסא, but it is a unit of measurement used for artichokes. Seriously.

The word is a corruption of קינרס "artichoke," from the Greek κινάρες (accusative plural), cognate with the word for 'artichoke' in many languages, and familiar to me from my days working in a liquor store, where we sold (though no one bought) Cynar, an Italian apero (bitter apéritif) flavored with artichokes.

At this point I'm tempted to say something flaky about the journey being more important than the destination, although I generally hate stuff like that. So instead I'll quote the Franklin aphorism in full, which like its Talmudic counterpart, has a rarely quoted second part:

"A word to the wise is enough, and many words won't fill a bushel."

And on that note:

"Of making of books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh." Ecclesiastes 12:12.

A Postscript

Wikipedia gives the following Latin versions of the saying:

Terence Phormio, IIII.3: Verbum sat sapienti.

Plautus Pseudolus, Act I.1: Dictum sapienti sat est.

Thomas à Kempis Imitation of Christ (c.1481), 3.34: Intelligenti satis dictum est.

Franklin could have gotten it from any of these. Or made it up himself. In fact, the Talmud could have gotten it from either of the first two. Goddammit. I wrote my damn BA thesis on the possibility of Greco-Roman influences on the Talmud, and I never knew about this. Just goes to show you: you can't spell "blah blah blah" without BA. Or "a bad grad student" without ABD.

On the other hand, this supports a pet theory of mine that most famous quotations usually have countless antecedents. I have a number of other theories about famous quotations, which will be the subject of my next post, unless anyone has any requests.